Data protection in the European Union has been a hot topic for years — and also a source of some confusion. Fortunately, the General Data Protection Regulation that will come into force in May 2018 will go a long way in clarifying the rules for protecting personal data. This includes clarifying the extent to which our data may be collected, what safeguards must be in place for its storage, how we can access and correct it, and more. In Europe, the legal regime upholding the fundamental right to data protection rests on how we define and interpret what constitutes personal data. However, 21 years after the EU’s first data protection law was established, grey areas remain. One regards Internet Protocol (or “IP”) computer addresses, the way that devices are identified on a network.

Static IP addresses — those that remain with the device indefinitely — have already been identified as personal data. But what about dynamic IP addresses — those that can change each time a device connects to a network, every few weeks, or anywhere in between?

Seeking clarity on that question, Patrick Breyer, a member of the German Pirate Party, filed proceedings against the Federal Republic of Germany regarding the government’s registration and storage of his IP address when he accessed several internet sites run by German federal institutions. Breyer argued that a dynamic IP address can identify an individual to the degree that a government storing the address constitutes a violation of data protection rights.

The verdict: dynamic IP addresses can be personal data

The case was brought before the Court of Justice of the European Union, which has now issued its judgment. The court ruled that a dynamic IP address can indeed be considered personal data when it can be linked with other information that a user provides while viewing a website — because a combination of factors can identify an individual. The Article 29 Working Party seems to support this interpretation, agreeing that a person is identified when the individual can be singled out from a mass of other people, not just by name or address.

A caveat: the legitimate interest clause

Because dynamic IP addresses have been found to be personal data, their collection and use must therefore be governed by strict rules. However, the court pointed out to some important caveats, detailing how dynamic IP addresses can be collected without the user’s consent and still meet EU (or German) data protection standards.

Website operators can collect and keep IP addresses without users’ consent when it is necessary to facilitate the specific utility of the given page. This exception falls within the infamous “legitimate interest clause” which limits users’ control over their personal information by letting companies or websites collect information without users’ knowledge. Referred to as the Trojan horse of the 1995 EU data protection law, this measure unfortunately remains in the recently adopted General Data Protection Regulation, albeit with a limited scope of application.

Even though the legitimate interest clause opened the door to a wide range of abuses, it is sometimes justifiable as a technological necessity. It is common practice for website operators or system administrators to log IP addresses to ensure the integrity and diagnostics of their systems and network. While logging IP addresses does not prevent attacks per se, it does help administrators diagnose issues, including everything from minimal disruptions in service to simple configuration problems of operating systems. IP addresses are also recorded in packet dumps, in temporary files, and in swap space; and they are used in routing tables, configuration scripts, protocol headers, firewall rules, and in a myriad of other places to enable systems to function. The legitimate interest clause means that when we cannot modify systems so that they do not record IP addresses, they can retain functionality.

Next for privacy in Europe: reviewing the e-Privacy Directive

While this case has brought closure to a long standing question regarding privacy and IP addresses, there are developments ahead that will bring more challenges, and more clarity, for our rights online. Next up is review of the e-Privacy Directive, the single piece of legislation that protects privacy and the confidentiality of communications in the EU.

In an era of new apps and the Internet of Things, revision of the e-Privacy Directive has the potential to harmonise and strengthen key privacy rules, such as rules regarding collecting and using metadata in the EU. It could also help promote the use of tools with “privacy by design”, and reinforce users’ control over personal information, whether we are browsing the web or communicating via messaging applications such as Skype, Whatsapp, or Signal.

Stay tuned for updates on the e-Privacy Directive, and get ready to help stand up for our right to privacy online!

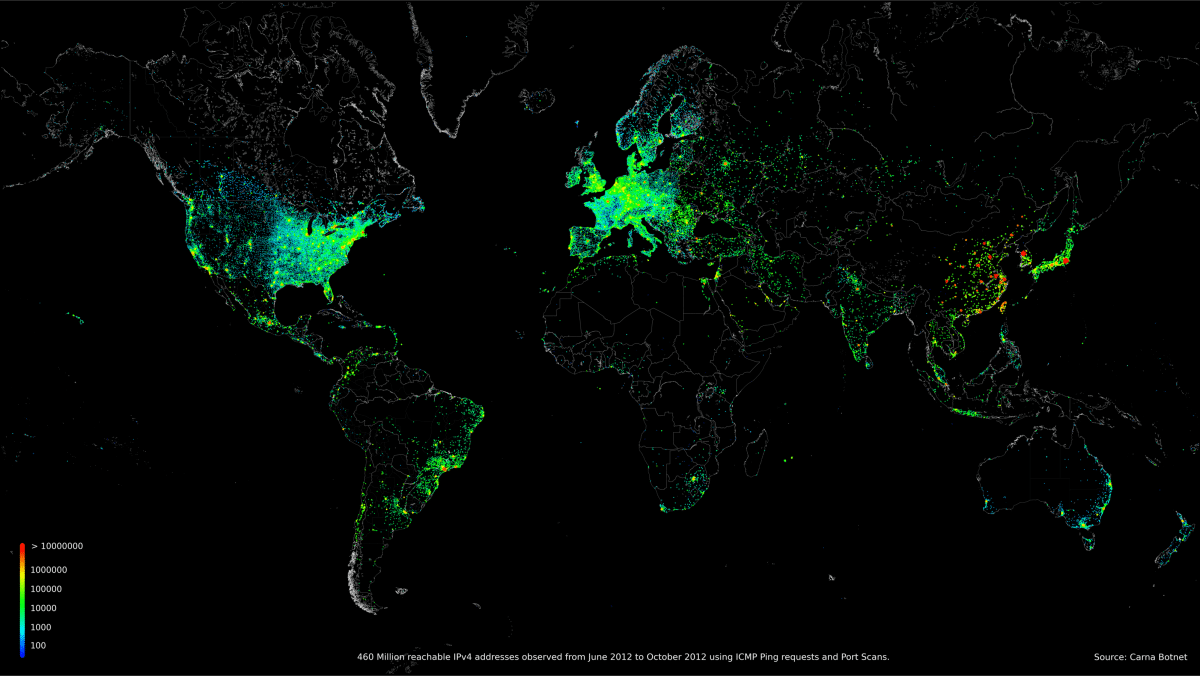

Image source: 2012 Internet Census