A high-level committee at the United Nations is expected to adopt a convention on cybercrime before the 79th session of the UN General Assembly. The current draft cybercrime convention has serious flaws that could legitimize harmful surveillance, undermine human rights, and hurt security researchers and whistleblowers around the world. Unless the convention is reformed, delegates must reject it. A bad convention is far worse than none.

Read our FAQ below to learn what the cybercrime convention is, what’s wrong with the current draft, and how journalists, human rights defenders, and other members of civil society can prevent a harmful convention from being adopted.

Q: What is the UN cybercrime convention?

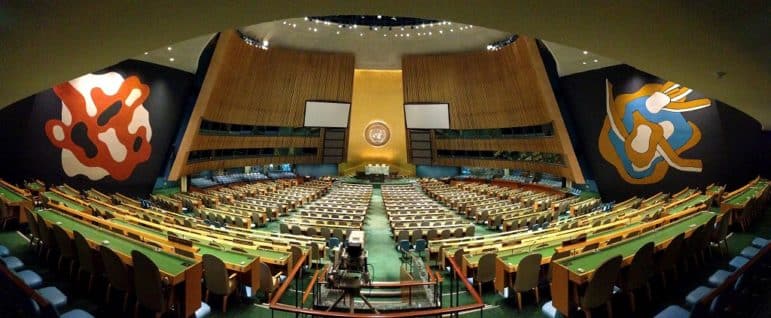

It is a global instrument envisioned by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) to aid international cooperation in preventing or investigating cybercrimes. To deliberate and craft the convention, the UNGA constituted the Ad Hoc Committee (AHC) on Cybercrime in December 2019, responding to a resolution advanced by the Russian Federation.

Since February 2022, over the course of six sessions, the AHC has negotiated the objectives, scope, and structure of the cybercrime convention, also referred to as the UN cybercrime treaty. The AHC was set to vote on a final version of the treaty during the concluding session, but the session was suspended in favor of further discussion.

The AHC will reconvene the concluding session for up to 10 days in the coming months.

Q: How does the current draft for the convention

undermine human rights?

In light of the discussions during the seven sessions of the AHC on cybercrime, the committee chair published the current revised draft and several proposals for compromise. However, the draft still fails to address many of the significant concerns Access Now and other civil society organizations have raised.

Specifically, the draft is overbroad in its scope of criminalization, yet contains insufficient safeguards for protecting human rights and digital security research. It also fails to adequately acknowledge that governments can and have used purported “cybercrime” laws to enable unlawful surveillance, improper persecution, or harassment of security researchers, as well as to target journalists, activists, and civil society more broadly. A cybercrime convention without clearly defined focus and standards would not only fail to prevent cyber harms but also pave the way for legitimizing right-harming legislations and actions by member states.

If it is not revised before adoption, the convention could also threaten people and communities already at risk of human rights violations. To understand the potential implications for LGBTQ+ and gender rights, read Derechos Digitales’s research on cybercrime regulation as a tool for silencing women and LGBTQ+ people, EFF’s post focusing on the potential impact of the convention in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, and Chatham House’s recommendations on gender mainstreaming.

Q: Why is it important to demand amendments now?

Failure to amend the convention would mean we will have wasted a time- and resource-intensive opportunity to enable governments to work together on cybercrime, without criminalizing security research or endangering human rights.

And unless we speak up now to demand these changes, the resulting convention will actively impede initiatives to strengthen cybersecurity by enabling the persecution of people who research digital security gaps, among other risks. In other words, a bad convention would leave us worse off than we are now, making everyone more cyber-insecure.

Q: What principles should the AHC follow to reform the cybercrime treaty?

- Keep a narrow focus on cyber-dependent crimes

To ensure international consensus and prevent misuse to undermine legitimate activities and human rights, the convention should focus only on criminalization of cyber-dependent crimes, i.e. crimes that are made possible by use of information and communications technologies, or ICTs. Crimes that have been transformed due to use of ICTs, i.e. cyber-enabled crimes, should not be included, to avoid state abuse and misinterpretation. Similarly, the convention’s scope should not include content-related measures, like provisions criminalizing mis/dis/malinformation, that governments can easily exploit. - Include safeguards for the cybersecurity community

The convention must not lead to an international legal framework that enables the persecution of the information security community: researchers, whistleblowers, activists, and journalists. Along with clear and heightened requirements around “intent,” the convention should also have a high bar for what constitutes “unauthorized access” and include margins for good-faith research.

To learn more, read civil society’s joint letter to the AHC Secretariat. - Adhere to principles of necessity, legality, and proportionality

The convention must incorporate robust safeguards applicable to the whole treaty to ensure that cybercrime efforts align with the standards of legality, necessity, and proportionality. Any international legal framework on cybercrime cooperation must ensure appropriate accountability, remedy, authentication, and oversight in legal assistance. Protection of privacy and personal data must be codified in the text. - Do not create a global surveillance framework

The convention must not endorse measures that would authorize or facilitate international surveillance of legitimate activities. This would include excluding provisions that would allow mass collection and retention of log data, or force technology providers to collect identity information. In addition, the convention must not undermine encryption or introduce vulnerabilities in systems that states or non-state actors could exploit. This would actively undermine cybersecurity and enable cybercrime. - Incorporate strong human rights protections

The convention must ensure human rights are incorporated in procedural measures and provisions on international cooperation. At minimum, it must call on member states to ensure that their implementation of obligations under the convention accords with international human rights law. The convention must raise, not lower, protections against arbitrary or unlawful interference and prosecution.

To learn more, read Access Now’s submission to the AHC on criminalization, procedural measures, and law enforcement.

Q: What can journalists, human rights defenders,

and others do to ensure that the convention is

amended in a rights-respecting manner?

If you are a human rights defender who wants a rights-centric cybercrime convention, amplify the concerns raised by civil society organizations by sharing our joint statement.

If you are a journalist who wants to cover the adverse impact the proposed cybercrime treaty could have on global cybersecurity and human rights, write to us at press[at]accessnow[dot]org.

If you are a member state delegate who wants to propose a meaningful change to the draft text, write to us at un[at]accessnow[dot]org.