Last week, an investigative report by ProPublica revealed that the internet company Cloudflare provided services to the hate group website The Daily Stormer. In addition, the report revealed that Cloudflare may have inadvertently been exposing people who filed complaints against The Daily Stormer to abuse by revealing their personal email addresses. The Daily Stormer is alleged to have harassed and frightened these people in retaliation. After Cloudflare’s general counsel Douglas Kramer defended offering services to hate groups in the name of free speech, the company committed to changing its abuse reporting policy in a lengthy blog post by CEO Matthew Prince. The company’s behavior is a case study about the importance of how anonymity and hate speech can affect users at risk — and reveals how much tech companies still have to learn to meet their responsibility to respect human rights and remedy abuses.

Background

Cloudflare provides a variety of services, including serving as a Content Delivery Network, which ensures rapid and stable delivery of websites to their users, and offering protection against hacking such as Distributed Denial of Service (DDOS) attacks on its customers. Cloudflare offers certain services for free, and provides paid accounts to larger clients. Cloudflare also provides free DDOS protection through its Project Galileo to non-profits around the world, including Access Now and our partners.

Should internet services be liable for having hate groups as customers?

Companies like Cloudflare are shielded from liability of content that passes over their networks through safe harbor provisions such as Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act and the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. Under these laws, if Cloudflare is notified about content that violates the law — often a copyright violation — it has a duty to take steps to remove it. This also includes child pornography, in which the company must notify authorities such as the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. This compromise of shielding internet intermediaries from liability fostered the creation of the web because of the sheer volume of content that moves across internet services — for example, YouTube has 400 hours of video uploaded every minute. Cloudflare is an intermediary that argues its services should be seen “more akin to a network than a hosting provider.” But this issue, in some respects, calls into question the strength of intermediary protections on offer.

As CEO Matthew Prince writes in a blog post:

From time to time an organization will sign up for Cloudflare that we find revolting because they stand for something that is the opposite of what we think is right. Usually, those organizations don’t pay us. Every once in awhile one of them does. When that happens it’s one of the greatest pleasures of my job to quietly write the check for 100% of what they pay us to an organization that opposes them. The best way to fight hateful speech is with more speech.

We don’t know if Prince has really sent such checks, but it is a spirited defense of the First Amendment and, more broadly, liability protections for intermediaries. Unfortunately for users at risk — and likely some of the victims of retaliation who complained to Cloudflare — such a principled stance did not protect their anonymity.

How the old abuse reporting form worked

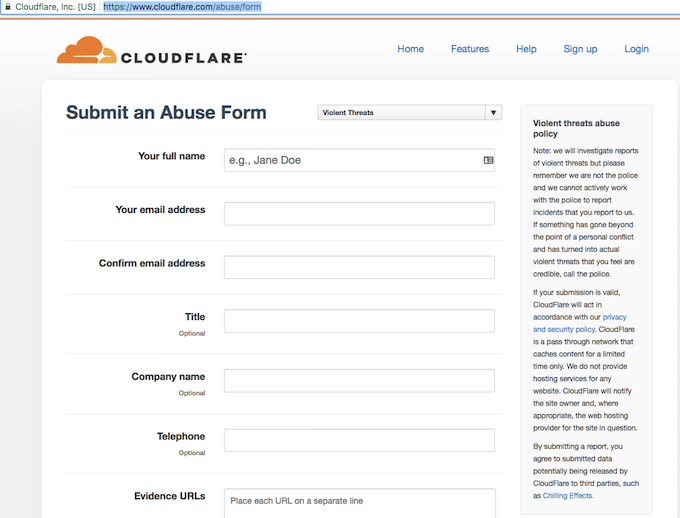

Cloudflare allows anyone — including non-customers — to submit an abuse form to offer a variety of options to choose from, including “Violent threats,” “Child pornography,” and “General.” Once submitted, Cloudflare previously used to pass along the email address, which is required to submit the form, to the hosting service of the website, not to the owner of the website (at least in the case of violent threats and child sex abuse). For example, a complaint about a site called BaseBallBats781.com might mean forwarding the complaint to a hosting service Geocities.com, instead of the actual owner of BaseBallBatts781.com.

As CEO Matthew Prince writes in his blog post, “What we didn’t anticipate is that some hosts would themselves pass the full complaint, including the reporter’s contact information, on to the site owner.” This means that Geocities.com would forward the complaint directly to the owner of BaseBallBats781.com. The folks running BaseBallBatts781.com then had enough information to identify and harass the complainant — which is what The Daily Stormer appears to have done, according to ProPublica. Aware of this threat to complainants, Cloudflare responded to this minority of cases by including a disclaimer on the abuse form that warned users how Cloudflare shared the information. Otherwise, the company does not appear to have made any broader changes to its policy or practices at that time. And some of these users didn’t read the disclaimer, according to ProPublica.

One reason Cloudflare utilized these policies is that its abuse system was partially automated because of the heavy volume of cases its Trust & Safety team would receive. “The reality is that requiring an individual working on our Trust & Safety team understand the nature of every site that is on Cloudflare is untenable,” as Prince writes.

Why techies need to talk to real people

In an interesting twist, it appears that Cloudflare had considered the need for some users to submit abuse complaints anonymously. And yet, the company assumed these users would use a fairly sophisticated technical solution:

… if you wanted to anonymously report something, you would use a disposable email and a fake name and submit a report to the site’s hosting provider or the site itself. We didn’t do anything to check that the contact information used in reports was valid so we assumed, with the disclaimer in place, if people wanted to submit reports anonymously they’d do the same thing as they would have if Cloudflare didn’t exist.

The company assumed that users would “use a disposable email” and “fake name,” which is a solution that only a small percentage of users would do or even know how to do. Moving forward, Cloudflare should sit down more with users at risk and victims to develop ways to meet their needs — which should be easy given the widespread adoption of its Project Galileo by nonprofits around the world. There are plenty of groups (including Access Now) who would gladly facilitate such conversations.

The new reporting form

Though companies are not directly liable to human rights treaties, they do have the responsibility to respect human rights, which they meet by doing due diligence — for example, understanding how clients like The Daily Stormer adversely impact people’s lives — and adopting policies and practices to prevent, mitigate, and remedy those harms. Providing the public with an avenue to direct complaints to Cloudflare, as well as to its unsavory clientele, educates the firms on how they’re impacting human rights, giving valuable feedback that smart, principled actors will use to improve their practices.

In this case, Cloudflare pledged to implement a new abuse reporting form in response to the ProPublica article. The company decided that “The person making the abuse report seems in the best position to judge whether or not they want their information to be relayed.” This is an important acknowledgement that users at risk often hold the best solution to their own problems. We examined the new form and disclaimer once it went live this week.

We’re glad to see that Cloudflare includes clear methods for people to opt-in, which will help protect users at risk. People can now select whether or not to “include my name and contact information with the report” to either the website hosting provider, or the website owner. And the boxes are unchecked by default. This is an important change that we welcome.

However, the form once again assumes that the user will understand the difference between a website owner and a website hosting provider. A simple line of text could provide an example to inform users and clarify their choice. Beyond that, the form does not warn of the possible consequences of disclosing such information, namely that the recipient will be able to contact you directly. This may seem like nitpicking, but the abuse reporting problems may have stemmed from a lack of understanding as much as a lack of anonymity. Again, it would help to have a simple textual explanation, link to a hypothetical, or flowchart showing what happens after you press “submit.”

While not a perfect solution, Cloudflare deserves credit for continually updating and changing its policies related to abuse. The company has scaled quickly in just six years, attracting hundreds of millions of dollars of investment, and has adjusted its stance towards human rights as it has learned along the way. If human rights were baked into its policies and practices from the beginning, some of these concerns may have been avoided. It should not take an investigative article by a journalist to reveal a pattern of abuse, meaning Cloudflare ought to enhance its own human rights due diligence.

Recommendations

We recommend that Cloudflare:

Improve due diligence

- Undertake a human rights impact assessment across its platforms and services;

- Consult with users at risk and stakeholders impacted by Cloudflare’s abuse reporting form, and other policies;

- Engage with the human rights community about evolving notions of online hate speech and intermediary liability; and

Update policies and practices

- Use plain language, instead of technical terms, whenever possible to better inform users;

- Bake in human rights protections to any new policies and services, rather than relying on a model of scaling up first and addressing abuses later;

Remedy any adverse impacts and ensure non-repetition

- Acknowledge the harm that was caused to the victims, without qualification;

- Seek to provide an appropriate remedy to victims of retaliation from its abuse reporting form

- Consider joining a multistakeholder entity like the Global Network Initiative to ensure ongoing attention to its human rights impacts.