Activists around the world rely on social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter to communicate and advocate for their rights in repressive regimes, making their accounts prime targets for attack. Attackers who gain control of an account can silence and embarrass critics, and can also create uncertainty and spread misinformation. These hijacking attacks harm users at risk, including journalists, activists, and human rights defenders, but the effects can sometimes be mitigated through the automated account recovery processes developed by social media companies, such as online reporting forms.

Now, however, Access Now’s Digital Security Helpline has discovered that these attacks are evolving, and proving much harder to resolve. In Venezuela, Bahrain, Myanmar, and elsewhere, activists who try recover their social media accounts using standard recovery processes can remain locked out. With this new form of account hijacking — which we’re calling the “Doubleswitch” — victims don’t just lose control of their social media accounts. They also have a harder time recovering these accounts, and in some cases, they never get them back.

Case study: Venezuela

Access Now’s Digital Security Helpline identified this new form of attack through our work supporting activists in Venezuela, which is now undergoing a period of deep political unrest. This includes a presidential decree authorizing surveillance and censorship online.

On January 9, 2017, our helpline received a request for assistance from Milagros Socorro, a renowned journalist, who reported that her Twitter account had been hijacked.

A month later, we received a second request for assistance from Miguel Pizarro, a human rights defender and a member of Venezuela’s parliament.

Para quienes aún no lo saben, las cuentas de Twitter y Facebook de @MilagrosSocorro han sido hackeadas desde esta mañana. Atentos…

— Melanio Escobar (@MelanioBar) January 9, 2017

Access Now’s helpline regularly works on recovering social media accounts for our civil society clients. In fact, approximately 20% of helpline cases involve some form of account recovery. But these attacks were different.

In each case, the hijackers gained access to the victim’s Twitter account (it is unclear how). Both accounts were “verified” and marked with a blue seal in the user’s profile, and both had a large following. The hijackers then updated the account information by changing the password and the associated email address, locking out the legitimate user. The hijackers then changed the username of the accounts from @MilagrosSocorro to @DESAMORTOOT in the first case; and from @Miguel_Pizarro to @PizarroPSUV and then @BuscoAsao in the second.

Having gained full control of the compromised account, the hijackers exploited a feature that allows Twitter to recycle unused usernames. After changing the credentials of the accounts, the hijackers registered Twitter accounts using the original usernames, which were now freely available, and connected the accounts to a new email address. They were then able to impersonate Socorro and Pizarro. When these victims attempted to recover their accounts, Twitter’s confirmation emails went to the hijackers, who pretended that the issue had been resolved. The hijackers then proceeded to delete one of the original accounts, making it even harder for the victim to recover it.

#Ahora | Hackean cuentas de Twitter y Facebook de la periodista Milagros Socorro. pic.twitter.com/TFgMi9Zu8C

— Espacio Público (@espaciopublico) January 8, 2017

Twitter’s staff worked closely with the victims to help restore the accounts and ultimately we were successful. Unfortunately, the hijackers had already begun to spread false information using the hijacked accounts, including deleting legitimate tweets.

Anatomy of an attack: How “Doubleswitch” works

This new form of hijacking attack is not unique to Twitter, nor is it happening only in Venezuela. Our helpline confirms that it can also work on Facebook and Instagram. The key to a hijacker’s success, however, is the same: the attack renders the standard recovery mechanisms useless, allowing the attacker to maintain control of the victim’s account for a longer period of time.

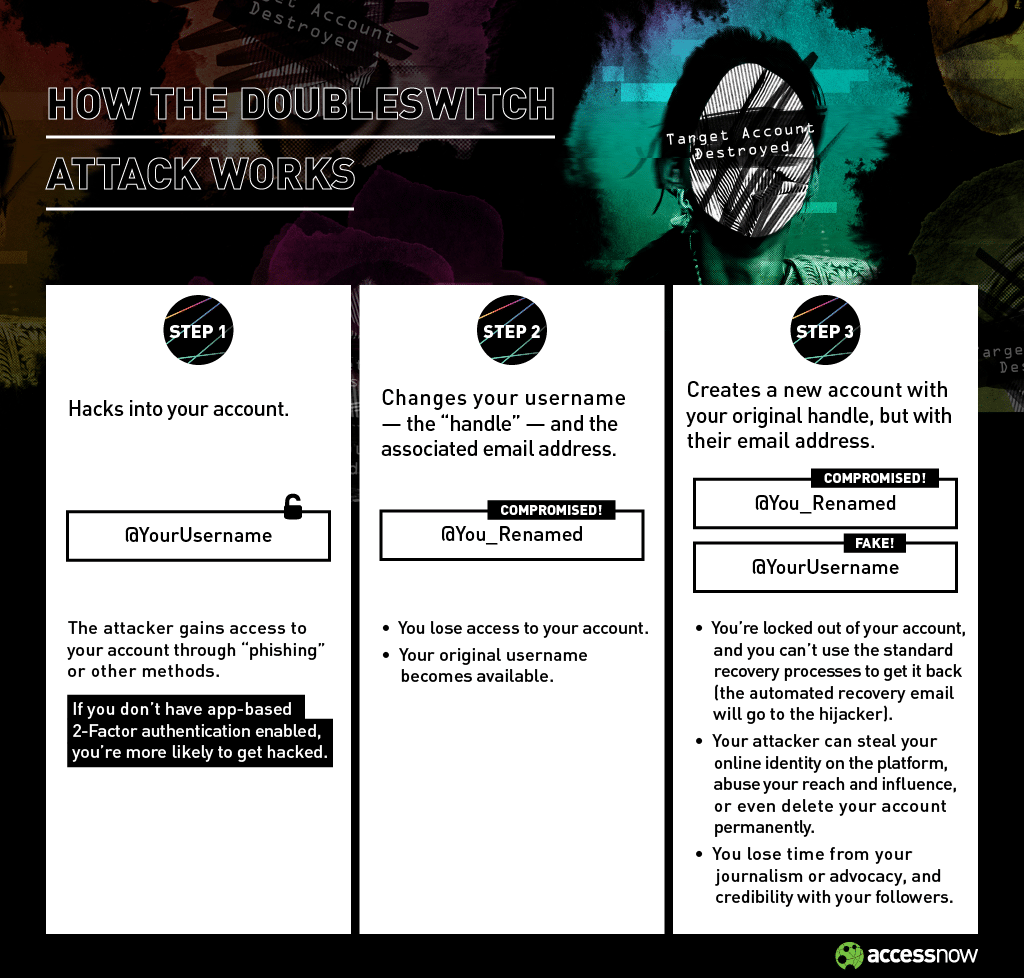

With the Doubleswitch attack, a hijacker takes control of a victim’s account through one of several attack vectors. People who have not enabled an app-based form of multifactor authentication for their accounts are especially vulnerable. For instance, an attacker could trick you into revealing your password through phishing. If you don’t have multifactor authentication, you lack a secondary line of defense. Once in control, the hijacker can then send messages and also subtly change your account information, including your username. The original username for your account is now available, allowing the hijacker to register for an account using that original username, while providing different login credentials. Now, if you try to recover your original account by resetting your password, the reset email will be sent directly to the hijacker. The infographic above gives you an overview of how this attack is conducted.

Agradezco el apoyo de @accessnow, @espaciopublico y @ipys en la recuperación de esta cuenta de Twitter. Mil gracias.

— Milagros Socorro (@MilagrosSocorro) January 11, 2017

There are serious consequences to this form of attack. Victims like Socorro and Pizarro lose time from their human rights work or journalism and the ability to communicate with their followers. The hijacker can exploit and abuse a victim’s reach and influence, damaging their reputations. Some victims may never recover the initial account, and even when they can, they must spend significant time and effort to do so.

Lessons from the Doubleswitch attack

So what can we learn from this?

- Hijackers can permanently lock out or extend the period of time they control a social media account by changing the username, and then deleting the original account.

- The Doubleswitch attack confuses potential followers and makes the standard recovery mechanisms ineffective.

- Social media platforms typically do not notify users of changes to their usernames.

- This attack is reproducible on other social media services, including Facebook and Instagram.

How to prevent Doubleswitch attacks: Our recommendations

We recognize Twitter’s ongoing efforts to work with civil society and to respect human rights. Companies are not a party to human rights treaties, but they do have the responsibility to respect human rights, and that entails adopting policies and practices to prevent, mitigate, and remedy harms that they cause or contribute to.

This new form of attack exposes some unforeseen gaps in Twitter’s policies and account features. It also illuminates gaps in security for other companies, and should serve as a warning to people using social media platforms. We accordingly recommend:

- Users at risk should enable multi-factor authentication to prevent adversaries from taking control of an account in the first place;

- Twitter — and social media platforms with similar account features, such as Facebook and Instagram — should update features and rules to address the Doubleswitch attack;

- To ensure a lasting solution, social media platforms like Twitter should consult with victims and relevant stakeholders while updating the policy, instead of doing so unilaterally, which may result in a short-term solution; and

- Social media platforms should also implement alternative ways to authenticate users, such as app-based authenticators, which do not require a phone number to implement. Phone numbers can expose the identities of users and place them at greater risk.

Media coverage

The Verge, Fortune, Wired, Mashable, Gizmodo, International Business Times, The Independent, Numérama, Silicon Beat, Post Internazionale, Hipertextual, Infosecurity Magazine, el Siglo, El Comercio, El Espectador, Schneier Blog

About Access Now

Access Now’s Digital Security Helpline works with individuals, activists, journalists, human rights defenders, and organizations around the world to keep them safe online. We provide digital security advice and rapid-response emergency assistance. The Digital Security Helpline is a free-of-charge resource for civil society around the world. Our 24/7 services are available with support in eight languages.

Access Now (https://www.accessnow.org) defends and extends the digital rights of users at risk around the world. By combining innovative policy, global advocacy, and direct technical support, we fight for open and secure communications for all.

We are a team of 40, with local staff in 10 locations around the world. We maintain four legally incorporated entities — Belgium, Costa Rica, Tunisia, and the United States — with our tech, advocacy, policy, granting, and operations teams distributed across all regions.