Image source: AlAraby

In August, the Danish Foreign Minister Anders Samuelsen confirmed that Denmark granted licenses for the export of surveillance technology that can be used against human rights defenders, activists, and journalists. Previously reported information confirms that licenses had been granted for sales to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Tunisia, Oman, Morocco, Algeria, and other states. The Minister indicated that Denmark granted the licenses because it follows a minimal interpretation of the current EU dual-use export assessment criteria (more below). This makes clear the urgent need for the current push to update EU export controls to address deficiencies and derivations like this at the member state level.

Evident-ly harming human rights

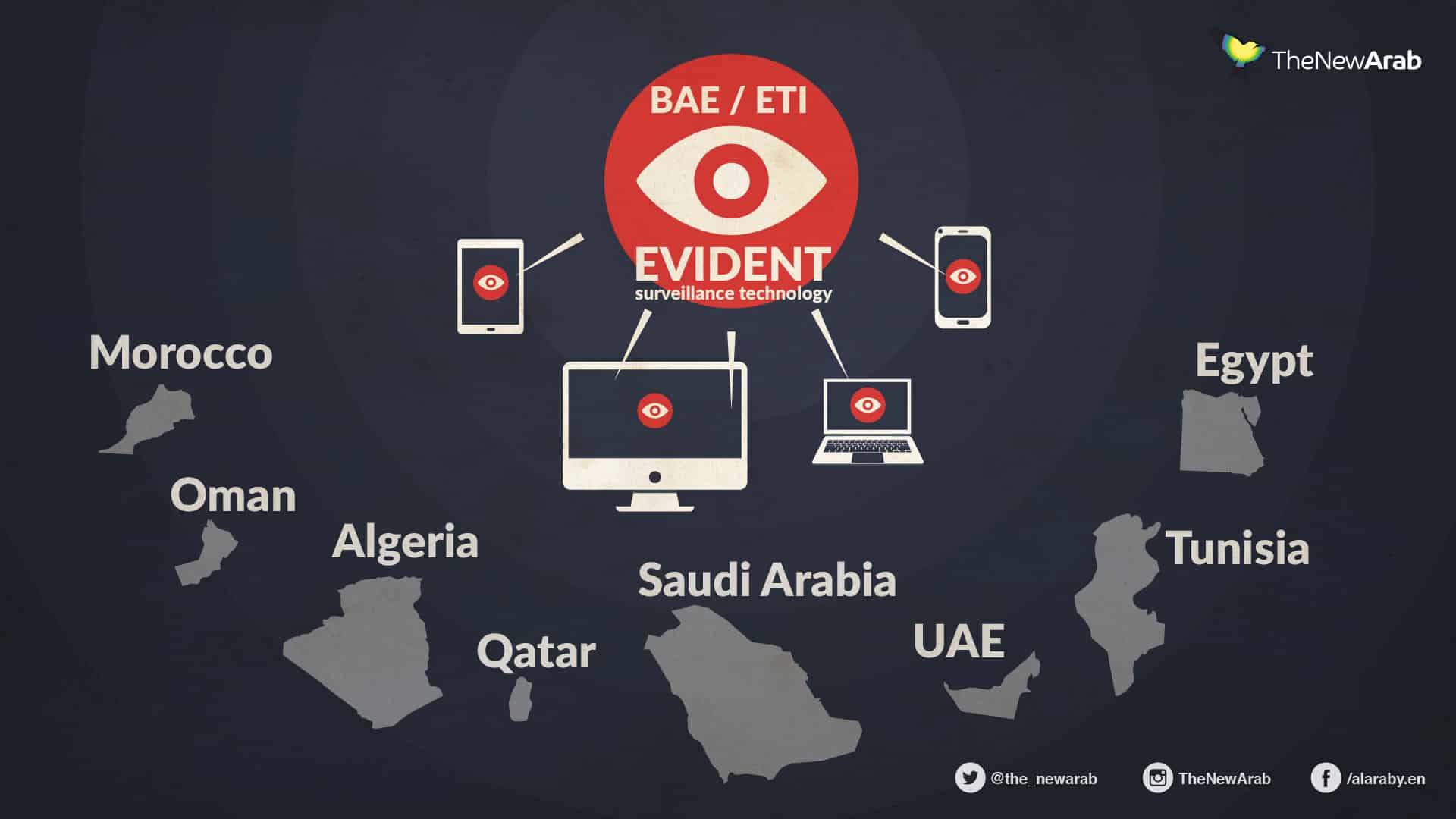

In June 2017 a BBC investigation revealed that ETI, a Danish subsidiary of UK-based BAE Systems, sold surveillance technology to several Arab states. The system in question, called Evident, is designed to assist authoritarian leaders in keeping tabs on citizens’ communications. As part of the investigation, the BBC revealed that Evident can intercept any internet traffic (even an entire country’s worth of traffic), pinpoint and track a target’s location based on cellular data, track an individual through voice recognition technology, decrypt messages, and more. The technology is easy to use; because data are indexed, a simple word or name search is all it takes to get a full online write-up of someone’s life and activities.

Why did Denmark lower the bar?

The existing EU regime for export controls contains a vague nod to human rights considerations for dual-use items, but allows for considerable member state discretion in applying established criteria for issuing licenses. Prior to 2014, Denmark had a strict interpretation of the EU rules, but then the Ministry of Foreign Affairs changed the policy without notifying the Danish Parliament. When the Parliament questioned the shift, Samuelsen wrote that “at a political level” [they decided] “to move away from a more restrictive approach” prescribed by the EU Regulation. The Parliament did not take the news well, saying that it represents a shift in Denmark’s approach to Middle East policy, and it should have been subject to Parliamentary debate.

The rationale for the shift appears to be that even authoritarian regimes deserve to be well equipped in the fight against terrorism, and it’s only an added benefit that selling to these regimes is a boon for the domestic technology industry. Helle Lykke Nielsen, an associate professor at the University of Southern Denmark and an expert in the Gulf States, points out that Denmark’s current regime is evidently focused more on the implications for the country’s own financial well being and direct security than it is on protection of human rights abroad. Yet, Nielsen writes, “There is no doubt in my mind that the regimes in Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf states primarily use it against ordinary political opponents”. Inadvertently, Denmark’s post-2014 interpretation could have dire long term consequences for users in Europe, just as much as those abroad.

Change on the horizon

As we note above, the EU is moving to tighten export controls, especially for export of cyber-surveillance technology to countries where the technology poses a critical risk to activists, journalists, and citizens. The European Parliament and the Council are currently examining the draft text for these controls, submitting amendments, and the text will be debated in the coming months and into 2018 (the European Parliament will be voting on the text in October and November according to the current timeline).

The draft text released by the Commission would address the issue of inconsistencies in domestic application by strengthening the human rights criteria to include violations of freedom of expression and privacy, imposing the need to deny or prohibit licenses when these human rights risks are present, and extending the existing “catch all” mechanism (under which previously non dual-use items can be “caught” for licensing consideration) to the technological part of the text. If these changes can withstand the coming political negotiations, they would help safeguard the human rights of vulnerable people and communities everywhere.

Civil society has been overwhelmingly supportive of the current effort. The focus of our coalition’s commentary has been to reinforce the Commission draft and to further recommend that:

- Human rights protections be strengthened and have definitive impact

The proposal should make clear that states are required to deny export licenses where there is a substantial risk that those exports could be used to violate human rights; where there is no legal framework in place in a destination governing the use of a surveillance item; or where the legal framework for its use falls short of international human rights law or standards. - All relevant surveillance technology be covered

A mechanism to update the EU control list should be agreed, which will decide on updates to the EU control list in a transparent and consultative manner, taking into account the expertise of all stakeholders, including civil society, and international human rights law. - Greater transparency and reporting is made mandatory

Greater transparency in export licensing data is needed. Such transparency is crucial in enabling parliaments, civil society, industry, and the broader public – both in the EU and in recipient countries – to meaningfully scrutinise the human rights impact of the trade in dual-use items. - Security research and security tools be protected

To reinforce the protection of research as stated in the preamble, the new regulation should include clear and enforceable safeguards for the export of information and communication technology used for legitimate purposes and internet security research.

Other lax regimes

Denmark is far from alone in demonstrating the harm of the current EU regime. For instance, in Bahrain, activists have been targeted by FinFisher, software created by Gamma international and marketed exclusively for remote monitoring and keylogging operations. Privacy International has spearheaded a civil society challenge of Gamma at the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development where — for the first time — the OECD found a surveillance software company to be in violation of human rights guidelines.

More people are becoming aware of the human rights impact of the trade of cyber-surveillance technology, in Europe and around the world. We are seeing this reflected in the media, with an in-depth investigation by De Correspondent, Security for Sale, and the Al Jazeera investigation, Spy Merchants.

We’re excited to see awareness increase, and we will continue to support the initiative to recast the EU dual-use policy and tighten controls so that Europe can uphold its human rights obligations around the world.